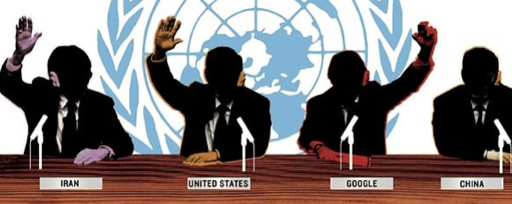

Nerd Diplomacy: Google’s Foreign Policy

In early 2010, when Google had decided to pull out of the China market, there was a brief window of discourse in which people discussed how this tech company in particular was becoming a quasi-state.

Google’s decisions from Mountain View, California affect lives + governance throughout the world. Its product decisions have far more ramifications than almost any other business’ product decisions. They influence foreign citizenry + governments.

Aside from just how the products are coded, sold + managed, WHERE the products are distributed and the services are offered is also a governance-affecting decision.

If Google chooses to operate in a country or not (like in China), or if it chooses to selectively tailor, edit, and reduce its products + services for another country (like, say Turkey), this is a governance decision. By offering its services to a certain country, it is potentially submitting itself to pressures, jurisdiction, threats, and negotiations with that country’s government. This could very well affect the livelihood of the citizens who use the service.

The New York Times tried to ascertain the state of Google’s Foreign Policy approach in March 2010. They assessed that Google began as Wilsonian idealists: believing that by interacting + engaging independent countries openly, they could spread democracy.

By early 2010, however, Google had grown more Kissengerian, with a realpolitik approach. They felt that you had to play with the competing interests — foreign entities will have divergent interests from yours, and you have to size up if these can be aligned to a satisfactory degree, or if its not worth the trouble — better to cut + run.

Or, another possible reading is that Google in early 2010 decided that it was firmly, strictly, anchoredly idealist. It was not willing to collude with a restrictive system like the Chinese government’s, just in order to gain advertising revenue profits + compete in the market.