My article on the potential for Design Thinking & Law is now published over at the ABA’s Law Practice Today, Innovation Issue.

Here is a copy of the article — head on over to Law Practice Today to read in full!

Introduction

When we talk about innovation and law, it’s easy to fall into a couple of fallacies. One is to assume we know who the audience for innovations are. We may make broad assumptions about who lawyers are, what their needs are, and what they want to use – based on our assumptions, rather than grounded facts and insights.

Another fallacy is perceiving technology as a savior, the magic wand to solve all problems. More apps, more algorithms, more software – it would be easy to think that these will rejuvenate how lawyers practice & how they serve their clients.

This is where design — and design thinking — hold great promise for aspiring legal innovators. Design provides the mindsets & methods that lead to greater understanding of who we are innovating for, and what the means (technological or not) we should be using to innovate. Design offers reliable, explicit ways to identify areas for developing products, services, and organizations, and to implement new ways of doing things.

Design should be of particular interest to two types of legal practitioners.

First, those who have ideas for how things could be done better – whether its ideas for how information could be managed better, for how services could be delivered better, or for a new legal startup.

Second, it’s for those who want to invigorate their practice, with more creativity, new ways of solving problems, and an eye to improved experiences for both attorneys and clients. Design offers lawyers a new perspective on how to work, and how to develop lasting relationships with clients.

What is Design Thinking?

Design, put shortly, is the practice of making things that are useful, usable, and engaging. It is domain-agnostic — it is about methods and outcomes, not about a particular subject-matter.

Design thinking has developed over the past decades as a set of design-driven methods and mind sets for use by non-designers. If capital d-designers spend years training in detail on the art of typography, or composition in communication design, or the mechanics of modeling a smartphone, design thinking is for those who do not want to devote their lives to producing new products, but who are interested in design methods as a means to innovation in their own field.

Design thinking is grounded in a handful of fundamental principles:

1) Be User-centered. Know who your user is, and orient your work to serve their needs– especially those that are unstated, and more meaningful.

2) Experiment. Be open to new ways of doing things. Watch for dysfunction and for opportunities, and use creativity to try to address them.

3) Be Intentional. Understand why you and your organization behave as you do, understand what your values are. Be deliberate in your actions, to keep your actions and values in alignment.

The promise of design thinking is that, using this approach, we will develop better ways of working, fresh ideas for what products and services you can be offering, a stronger organizational culture, and a more powerful and lasting relationship with users.

Design Mindsets

Taking a design-thinking approach means learning to inhabit a set of mindsets — many of which seem counter to those lawyers are trained to have.

Center Your Work on Your User: A design approach begins with the user. A user could be the customer who is buying your client, a supervisor who needs your work, or yourself. The user is the individual who will be using your work product.

Design thinking focuses on the user: for you to deliver to them something that will be useful and usable to them, first you need to understand them. This means caring deeply about their needs, their values, and their behavior. The more you can invest in user research, by observing how they operate and what they prioritize, the better you will be able to serve them.

The goal is to get beyond stereotypes and assumptions about who your users are. Rather, speak to them directly, and observe them in their habitat. The insights you gather in this work can help you redefine what problem you are trying to solve for your user, and also what type of solution would work.

Structure Your Process: Your work should be about solving your user’s problems – whether that means producing a document for them, getting them the answer to a question, or delivering a product to help them accomplish a task. So once you know thoroughly who your user is, and what they want to achieve, then you must focus on what the exact problem statement is.

When you have a task due, or a work product required of you, try to write out explicitly, who will be using your work product, what they will be using it for, and why it is important. In the language of design, this is a ‘use case’ statement. This statement should be your guide as you put the work product together, helping you focus on what is a priority and what is not. It should also keep you focused on your user’s needs, rather than getting distracted with other objectives.

Another process structure is the dual use of ‘focus’ and ‘flare’. There are times in a work process where there is value in sourcing lots of ideas, lots of feedback, and lots of insights – these are flare moments. In a flare phase, you can widen your vision to think of lots of ways to define a problem or to solve it.

Then, in a focus phase, the goal is to make clear decisions about what you will indeed work on. Being deliberate – making an explicit choice about what you are working on and why – will help guide you as you implement your solution. But before jumping too quickly to one, single, perfect solution, the flare phase allows you to be wild and creative, and potentially come up with breakthrough ideas.

Bias to Action: Rather than think and talk about what the best course of action to take, design-thinking advocates action. When you have an idea of what might work, try to implement it. Do it in a low-fidelity way, that does not require much time or resources. Make a first draft, and gather feedback about whether it is the thing you should be doing.

Design thinking also advocates be visual, over verbal. Rather than try to talk through a solution, drawing can help make manifest what the meaningful details are and focus on whether it is indeed a path worth pursuing. Visual thinking will help ideas become clearer, and help you communicate with your user in a richer way.

Feedback & Iteration Cycling: As you try to develop a solution to a problem, build a first prototype of a solution quickly – and then test it with your users. Being open to feedback will help you make sure you are on the right path to satisfying your user.

Before investing more resources in fully developing your solution, first test them with your user, and gather as much input about what’s working and what’s not. This feedback can then guide your next ‘iteration’ – a more developed version of your solution. You may even have to go back and redraft the definition of the problem you are trying to solve.

This mindset is not anti-perfectionist – there is still great value in attending to the details of what you are producing, and making sure they’re perfect. But before you get to the final, perfect version of your work product, first you should be testing, gathering feedback, changing your product, and cycling through that loop.

At first, taking feedback can be painful and awkward – hearing all of the things that annoy your users, that they don’t understand, or that they think are worthless. But design thinking trains you to consider feedback as a gift. It is your guide to how to make your work product better.

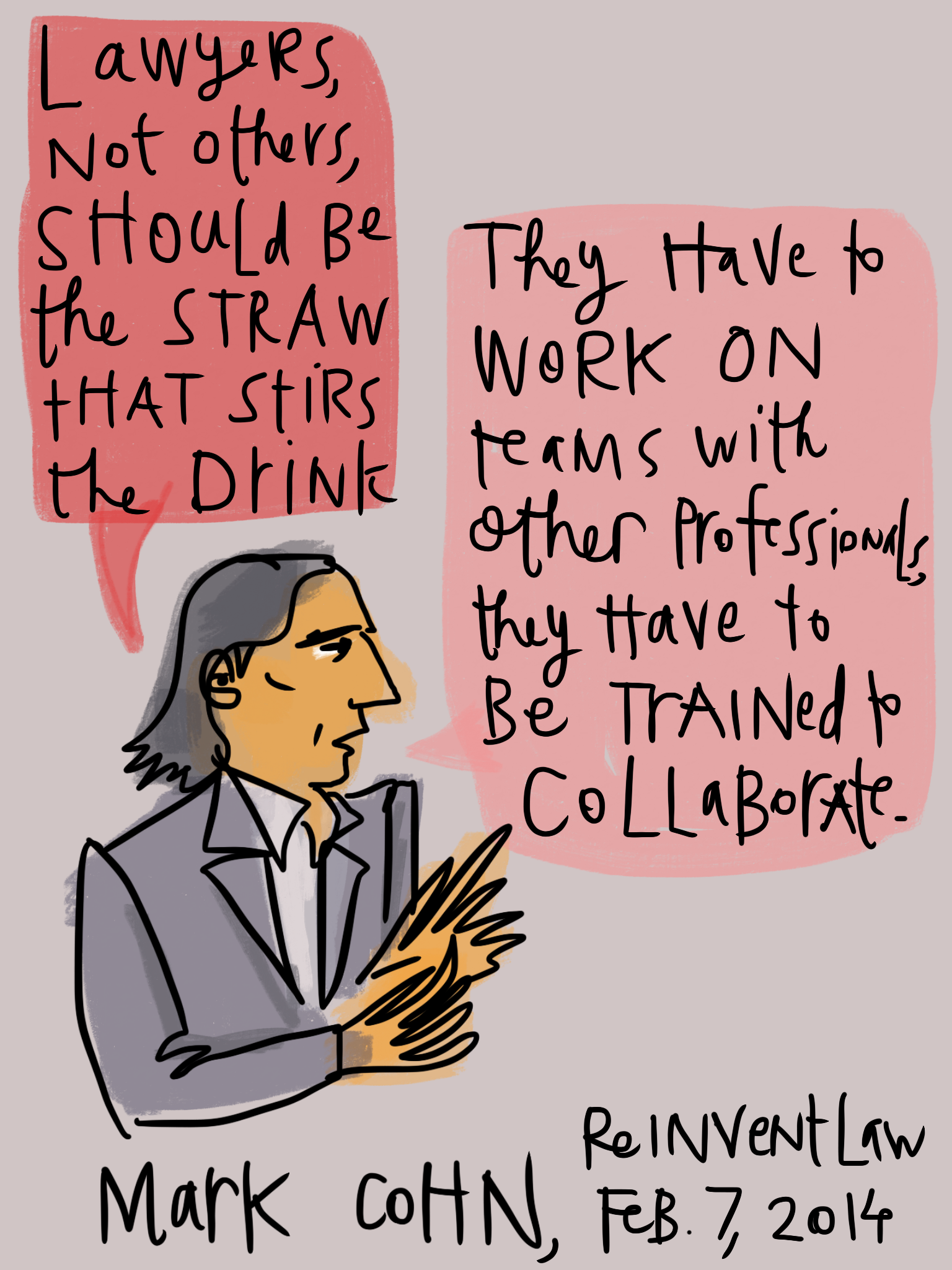

Interdisciplinary Collaboration: A team – especially one composed of many different types of domain-experts – can arrive at better solutions than an individual. If you are looking to innovate, then seek out collaborators who come from other fields.

Design-thinking puts a huge value on analogies — breakthrough ideas for how to solve problems in your field will likely not come from inside the field itself. Rather, consulting with people from other fields can give you fresh perspectives and new insights. We can find better ways of doing things, if we can find people with skillsets we don’t have – whether it’s engineering, business, art, or education.

Collaboration is not always intuitive – a lawyer’s approach to solving a problem may not always be at the same pace, or with the same priorities as those of an engineer. But there is great value in learning how to navigate interdisciplinary collaborations. Your collaborators will be able to see new ways for you to create value for your user. And they may know other ways to implement solutions, that can save you resources.

Law & Design

Design thinking has already been introduced to the fields of management, healthcare, and financial services. Design practice is being used to develop new ways to engage and serve customers, and to rethink how organizations operate internally.

Law — as a service-driven profession — is ripe for design thinking.

For those in law who have ideas for how legal services could be delivered in more effective, or more efficient ways, a design thinking approach can help you get from idea to implementation. Adopting design mindsets, you can start to prototype your idea, and test with your users – to see if your idea has legs, and if it does, to figure out a path towards developing it into a product that your users will love.

At a smaller scale, design thinking mindsets can also be integrated into daily work practices. You don’t have to be trying to develop a whole new product to use design. The next email you draft, think of it as a prototype. Who is your user? What do they need and value? What can you do to make your email more usable and useful to them? Can you seek out feedback to see what effect the email had on them, and what could have been better?

This approach may at first seem unnatural or burdensome – adding more procedure to a work day that is already busy. But the more you practice design thinking, the stronger your instincts will grow and, likely, the more worth you will see in taking a user-centered, responsive, and prototype-driven approach to work.

Design can be a main driver of legal innovation – in uncovering new services that lawyers can offer clients, defining new legal ventures that will serve consumers, and in creating new roles for JDs to play. It can also reinvigorate lawyers’ current work practice – building stronger relationships with clients, improving your communication with them, and putting a priority on the human experience of both the clients and the lawyers.

When we talk about innovation and law, it’s easy to fall into a couple of fallacies. One is to assume we know who the audience for innovations are. We may make broad assumptions about who lawyers are, what their needs are, and what they want to use—based on our assumptions, rather than grounded facts and insights.

Another fallacy is perceiving technology as a savior, the magic wand to solve all problems. More apps, more algorithms, more software—it would be easy to think that these will rejuvenate how lawyers practice & how they serve their clients.

This is where design—and design thinking—hold great promise for aspiring legal innovators. Design provides the mindsets and methods that lead to greater understanding of who we are innovating for, and what (technological or not) we should be using to innovate. Design offers reliable, explicit ways to identify areas for developing products, services and organizations, and to implement new ways of doing things.

Design should be of particular interest to two types of legal practitioners.

First, those with ideas for how to do things better—whether how to better manage information or deliver services, or for a new legal startup.

Second, those who want to invigorate their practice, with more creativity, new ways of solving problems, and an eye to improved experiences for attorneys and clients. Design offers lawyers a new perspective on how to work, and how to develop lasting relationships with clients.

3 Comments

I have been following and I am excited at this line of thinking – I have practiced now for 30 years and have always been disappointed in the degree of creativity in our profession – recently I changed my thinking and have tried to use that as an opportunity, it seem to be working (if for nothing but my own outlook!).

I just saw a comment in an art gallery that “creativity requires the freedom to make mistakes” – I realized that seems to encapsulate a significant problem – we lawyers (realistically or not) feel we can make no mistakes, and any will result in ridicule, alienation, and/or malpractice – I think that needs reconciled as a part of the discussion.

Yes — how the legal profession is regulated, and its unspoken culture all seem stacked against experimentation & creativity. But if we think about small-scale experimentation, like in how we practice & how we communicate with clients, we can start here. At the same time, though, we also need to be thinking at the high level, about how the regulations need to be changed to allow for more innovation.

Thanks for writing!

thank you for your time and energy on this – and for supportive comments – those are exactly what I have dramatically changed (formerly a managing partner of a large firm, now solo with an entirely new approach) – I really think the world may force these changes, less toleration of the profession’s traditional approaches – I’m on board!