I have been working with my Legal Design Lab and the National League of Cities to improve people’s access to housing justice and eviction prevention resources.

Especially with COVID-19 hardships, there are more renters at risk of being evicted. They’re behind on rent, they’re in an unstable economy, and they need help dealing with back-rent, fees, court cases, and the threat of homelessness.

City, state, and federal government agencies have responded with new programs. There are mediation services, legal counsel programs, rental assistance funds, navigator services, and other things — often called an ‘eviction diversion’ program.

This work has brought up the question of burdens.

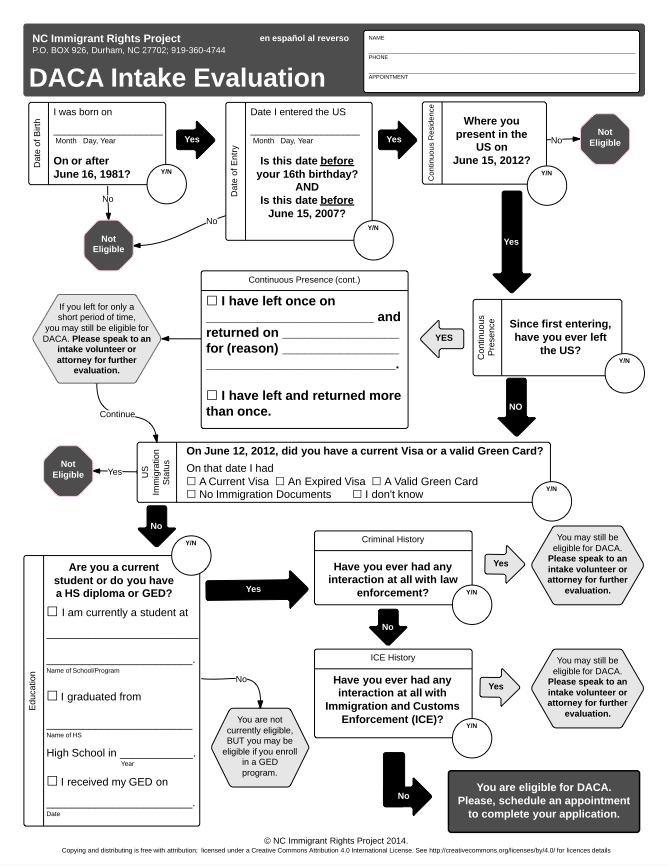

Especially for tenants, who are having financial hardships, many of these eviction diversion programs require tenants to do lots of things to get access to benefits.

To get rental relief, for example, it means a tenant must fill in lengthy applications, gather documents, following months-long procedures, negotiate with their landlord, and figure out eligibility formulas.

This goes back to the issue: how do we design the programs in practice — not just the overarching policies? The devil is in the details. The process often is a punishment. How do we roll out relief programs that actually achieve their intent of keeping people housed, avoiding adversarial court proceedings, and stopping harmful scarlet ‘E’ eviction judgments on people’s records? How do we make sure the programs stop spirals into poverty?

This takes us back to the question about administrative burdens. If a policy is rolled out in a high-burden way, that makes it difficult to: find out about the program, sign up for it, and follow through on it. Then many times the policy goal will be undermined. People won’t be able to use the benefit, they won’t be able to exercise their rights, and the bad outcome is going to happen anyway.

One key book to have on the table, then is the wonderful volume, Administrative Burden: Policymaking by Other Means, by Pamela Herd and Donald Moynihan.

Below are some key points to take away from the Administrative Burden book— though I recommend you get a copy for yourself to dive into case studies of various government and state benefits programs, and how they’ve grappled with the politics and administration of administrative burdens.

We need to focus on citizens’ experience of government policies & programs.

Their book points out that policy-making often focuses too much on the policies in the abstract and does not focus on their actual administration. There’s too much focus on the policyholder or the policymaker, and not so much on the citizen’s experience

More burdens are faced by those who have fewer resources to manage and overcome them. For many Americans, the experience of government is the experience of burden — a great quote from their introduction.

There are 3 main categories of burdens to track: Learning, Psychological, and Compliance Burdens.

We can measure how high- or low-burden a program is by looking at 3 components of a citizen’s experience:

Learning costs:

- Time to learn about the program

- Time to figure out if you’re eligible for it

- Time to figure out what benefits you’d actually get

- Time to access the program

- Time to determine what conditions you need to satisfy to get it

Compliance costs:

- How hard it is to assemble documents to prove you’re eligible, or what you should get

- Financial and transactional costs to get services to help you get through the application — like lawyers or navigators

- Travel costs to show up for interviews, file documents, get other supporting documents or fingerprints

- Financial costs of fees to apply or get documents

- Transactional costs to reply to communications from the program, meet deadlines, clarify requests

Psychological costs:

- Overcoming stigma or embarrassment of using a service

- Losing autonomy and privacy when opening one’s life to administrators evaluating them

- Frustration of dealing with repetitive, unjust, and unnecessary procedures

- Stress about uncertainty of whether one can make it through the process

- Sense of procedural injustice, of not having a transparent, respectful, and fair procedure

Some of these costs can be measured objectively, by gathering data about financial costs, time costs, and other quantitative measures. Others can be measured through surveys, interviews, and other design evaluations of people’s experiences.

Burdens matter to people’s use of government programs.

Burdens matter a lot. As policies and programs put more burdens on people, this affects whether people can actually get the benefits and rights that are at the heart of these policies.

And design matters to burden. This is a matter of user experience, good design, and community involvement. Good, community-centered, and creative design can shift burdens away from citizens and on to the government. How can we shift burdens to those with more resources to bear them? That’s most often away from citizens individually.

Design can help us measure burdens as we are creating new programs and services, and then evaluate them in their pilot stages. Are people being frustrated? Are they dropping out from onerous tasks? Are they becoming alienated from government services because of how burdensome a program is? We can use design techniques of user testing, ux evaluations, and human-centered evaluation to measure these burdens and create new strategies to repair them.

Every public service should have good citizen experience (and burden reduction) at its core.

As groups are making and evaluating new programs, they should be aware of citizens’ experiences and burdens. This means having these principles at the core of their work:

- The program should be designed to be simple

- Processes should be as accessible as possible

- The program should be respectful of the people they encounter, and dignity should be at the core

Design can again help here. This can be done through User Personas, User Journey Maps, trackers of where people are failing or falling off, surveys about stress and procedural justice, and measurements of wait times, and other objective measures of burdens.

We can create replicable strategies to lessen burdens and improve citizens’ experience.

How do we make Administrative Burdens & Citizen’s Experience part of front-line policymaking and service delivery?

The book points to a few directions:

- Training policy managers & on-the-ground administrators in the importance of the citizens’ experience, these 3 kinds of burdens, and the importance of good service design. There also needs to be explicit training in equity & burdens — about whether people from certain demographic groups are being asked for more evidence, put through more process, and asked to shoulder more burdens.

- Instituting more testing of burdens before and after a program rolls out. If we measure it, we’ll optimize for it. This means gathering data on the learning, compliance, and psychological costs – -through intentional data-tracking, running of surveys, mapping of user experiences and drop-offs, etc.

- Deploying burden-reducing strategies that can reduce these learning, compliance, and psychological costs. Some of these burden-reducing strategies include the following. Many of them draw on nudge/behavioral heuristics literature.

Burden-reducing strategies for public programs

- Limit eligibility criteria. Cut out unnecessary or overly burdensome ‘means tests’ that make people prove they are eligible based on various income and financial assessments

- Limit the amount of choices, reduce cognitive demands, and label what the most common choice is.

- Invest in community-based outreach, to make it easier to find out about the program and learn other people’s stories of it.

- Label and brand programs in positive terms, that reduce stigma, embarrassment, and moralizing.

- Auto-enroll people, presume they are eligible, and cut out tasks they must do to get access to the program.

- Figure out which party is well-resourced, and pass high-burden tasks around document uploads and financial accounting to them.

- Possibly do cross-overs between programs, integrating data from other programs so there’s no need to fill in forms with information the government already has, or upload new documentation.

Open Question: does lowering burdens on citizens mean trading off privacy?

One question to balance the burden discussion with is around people’s privacy, and control over their own data. Many strategies around lowering burdens means collecting and connecting data together.

Especially if it is poorer people applying for these programs and needing ‘burden-reduction strategies’ — it’s likely to be their data that is being handed off between programs in order to make it easier and quicker to use a service.

Does reducing burdens lead to a reduction in privacy from the government? What is the balance between an all-knowing government, in which agencies are passing off information about a person back and forth — and an easy-to-use government that is significantly easier to access? There’s a huge need for design sessions, technical solutions, and policy work around this trade-off, of low-burden government services that also protect vulnerable people’s privacy.