I have been attending many court innovation conferences over the past year, and taking notes about what points of friction + failure arise as the institutions try to be more experimental, and more human-centered in their work.

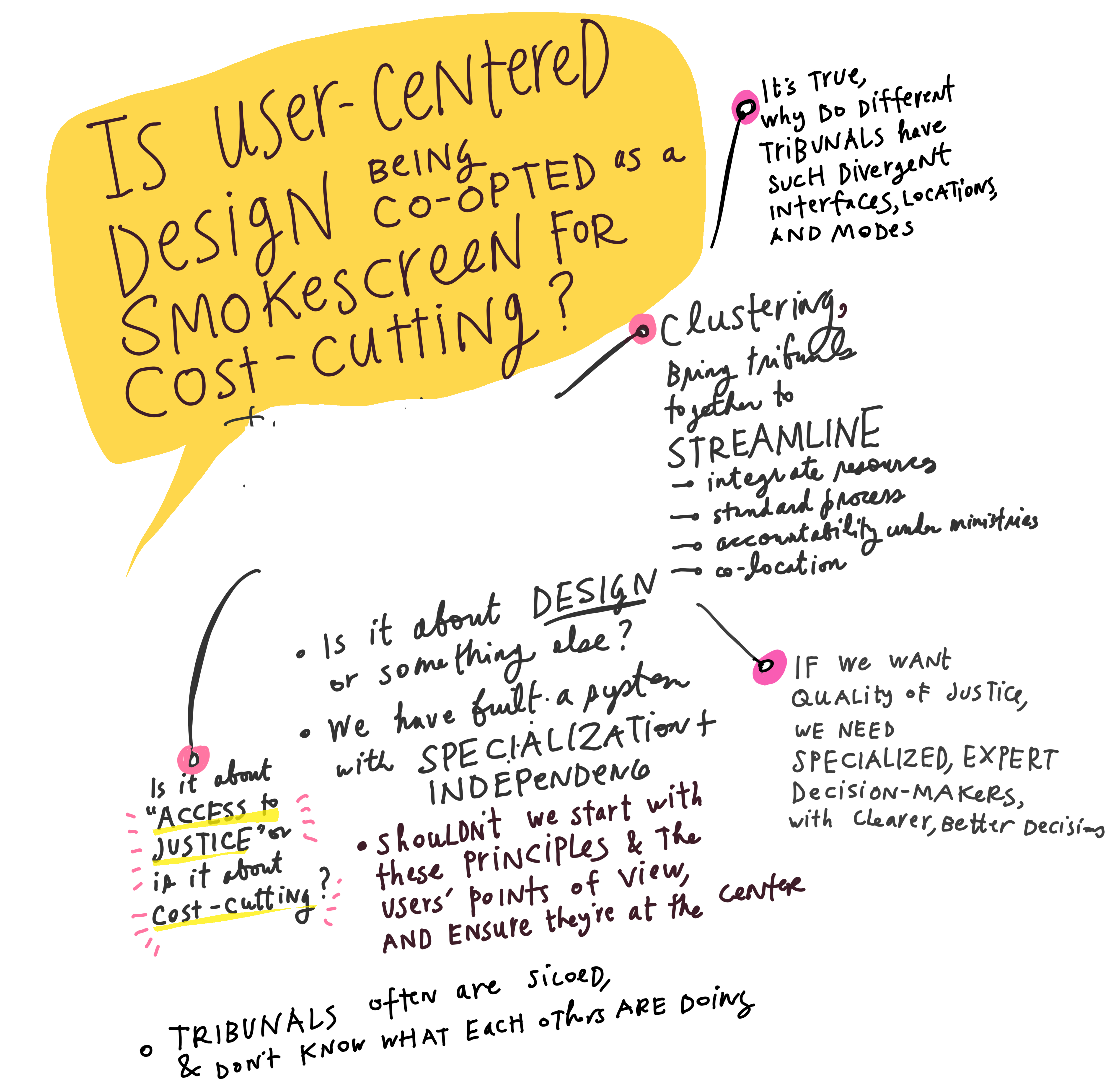

One very interesting point, that I had not expected, was the suspicion that the frame of ‘user-centered design’ as an innovation method might actually be a smokescreen for cost-cutting. That the dressing of innovation was a mean to placate staff and other stakeholders, while their budgets were cut and less human-intensive services were put in place.

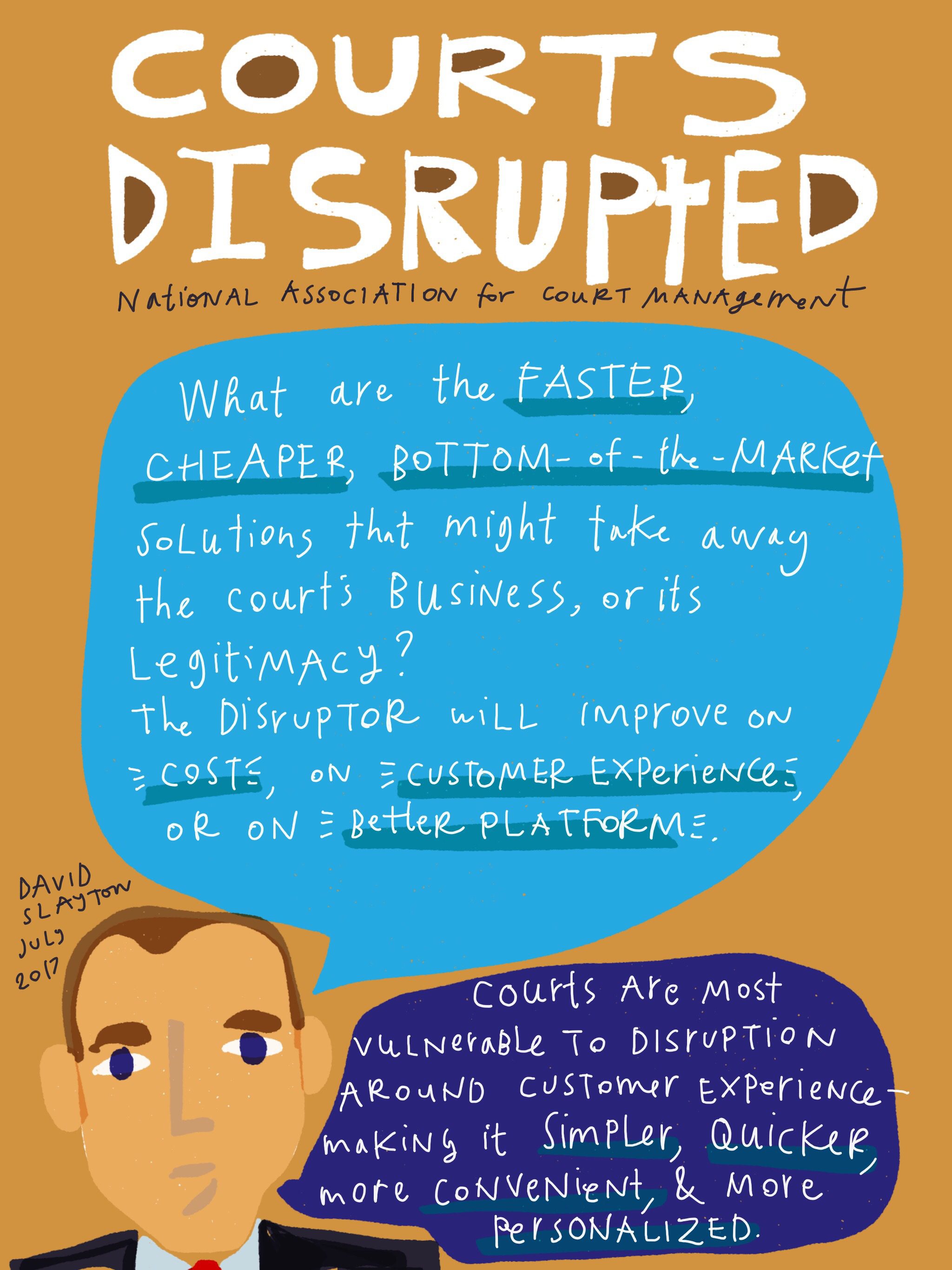

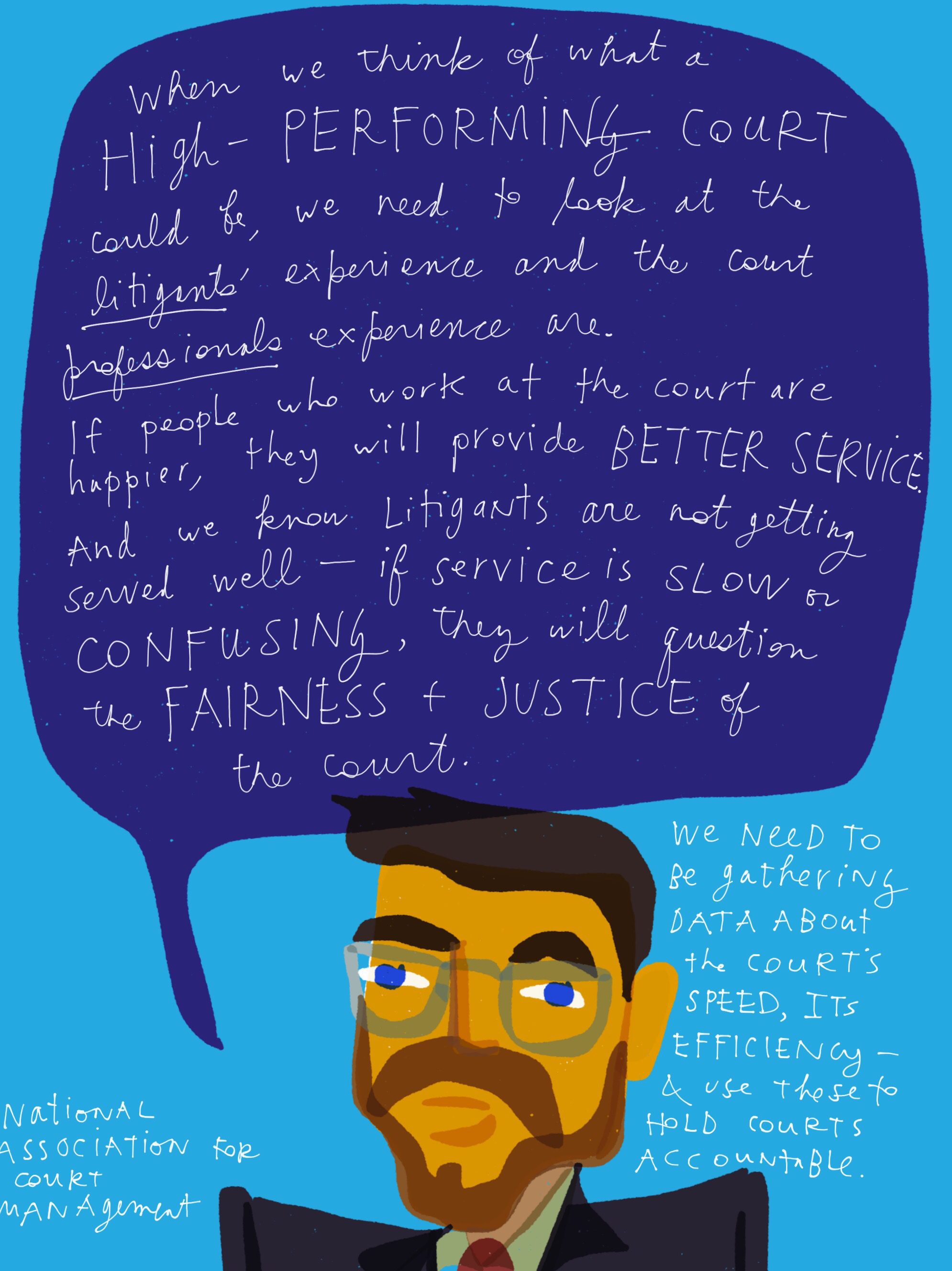

To me, this concern better fits with more general tech-oriented plans for court reform, in which AI, blockchain, data analytics, and other automation is brought in to ‘streamline’ services. User-centered design is better understood as a way of understanding how to make these new future investments in the court’s future versions, to serve people in the best way. Often, what user-centered design findings point to is the need to still have human-intensive (potentially expensive) services, that complement and support the tech-driven ones.

But the concern is not to be ignored: just because an initiative is carried out under the banner of ‘human-centered’ or ‘design and innovation’ does not mean that it leads to quality procedural or substantial justice.

Other major points of concern with design methods in court are the following:

- that courts have low tolerance for failure, and cannot waste public resources — so it is difficult to experiment

- limited budgets and overworked staff means that people don’t have the capacity for strategic, long term-oriented work

- the IT infrastructure is not modern or flexible enough to support the development of new applications on top of it

- human-centered design — especially participatory co-design — can be expensive

- there will always be trade-offs about who the main ‘users’ are, when prioritizing different possible designs, making it hard to be human-centered for all populations.

What are the other factors that make it hard for court leaders to run more pilots, to talk to their stakeholders, and to create more user-friendly services and policies?

1 Comment

Thanks for this post. What you observe is real, particularly in decentralized court systems. The conflict stems from the fact that staff doing simplification and reingeneering are not those familiar or focussed or responsible for access. So, one group focusses on improvements that make running the court faster and more efficient, and the access groups can be left out or are not part of those efforts. So building a bridge is essential for simplification efforts to include those working on the access issues to share and develop joint priorities and principles for tech based projects and the like.WA State is about to release new Technology Standards (updating the 2004 ones) soon–so maybe those can help other courts create their own tech standards and principles. Bottom line access issues are efficiency issues. Tom Clarke and others have written nice articles about related topics on reingeneering, fragmentation, the need for principles in the Future Trends in State Courts over the years. You might want to submit an article there? https://www.ncsc.org/trends