This afternoon, I had the privilege of hearing Professor Jay Mitchell of Stanford University (and director of the Transactions Clinic at the Law School) speak about the value of graphic design and sketching practices for lawyers.

Jay has a book, Picturing Corporate Practice, coming out at the end of February, that brings a design approach to corporate law practice. Read more about it here.

Here are my notes of what he said.

On the value of sketching

Think through drawing, not to be an artist, but to be a better thinker.

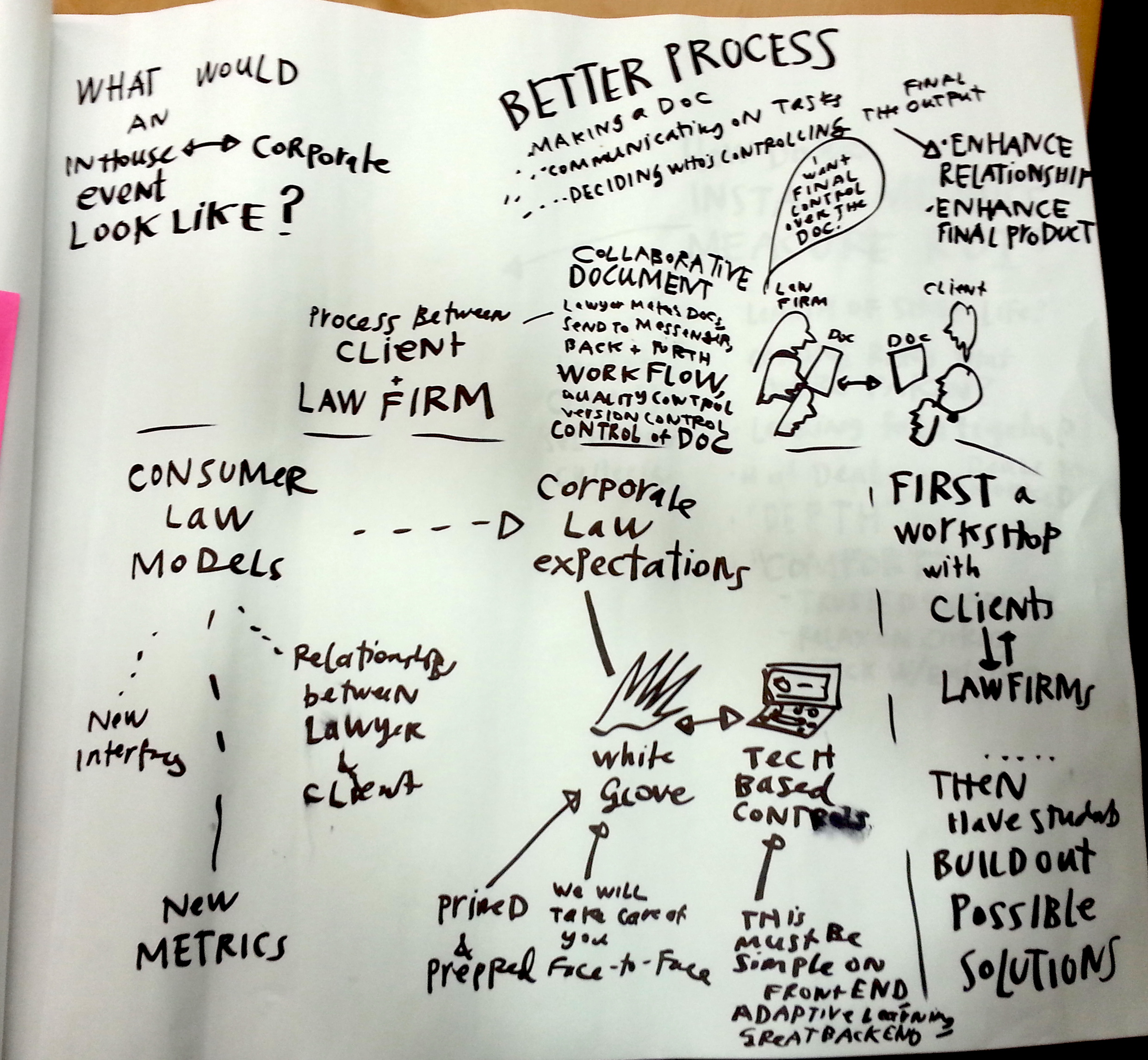

Once you draw a concept out, it forces you to have a conversation with yourself — to look at that sketch and think — how does this actually work? What would happen next?

Sketching also helps us with the physicality of it. When you’re drawing on a whiteboard, it allows you to be collaboratively on the same surface, and to communicate with emphasis.

Are sketching and visuals being used in law schools?

Many students write out their notes, some make sketches and charts. Others do it in clinics, making maps and charts for their clients, especially in the transactions clinic.

In law firms, some groups — like in patent litigation — embrace diagramming and visual presentations, so they can get complicated materials across to a lay audience (like a jury). But that’s because the practice group embraces the approach — it’s not usually like that.

One LLM commented that she was taught to make charts and graphs in law school, but that approach disappeared once she entered practice. There is more visual explaining and diagramming in school, but it gets lost in the office.

Visual design is good for learning law

Graphics help us understand all the moving parts we’re working with, and the relationships between them. It is a good way to ‘get going’ on a problem — see the landscape and figure out what to do.

It’s also a great way to share knowledge, from an expert to a novice. By making sketches and visuals together, you can understand each others’ mental models and processes.

Corporate lawyers need design

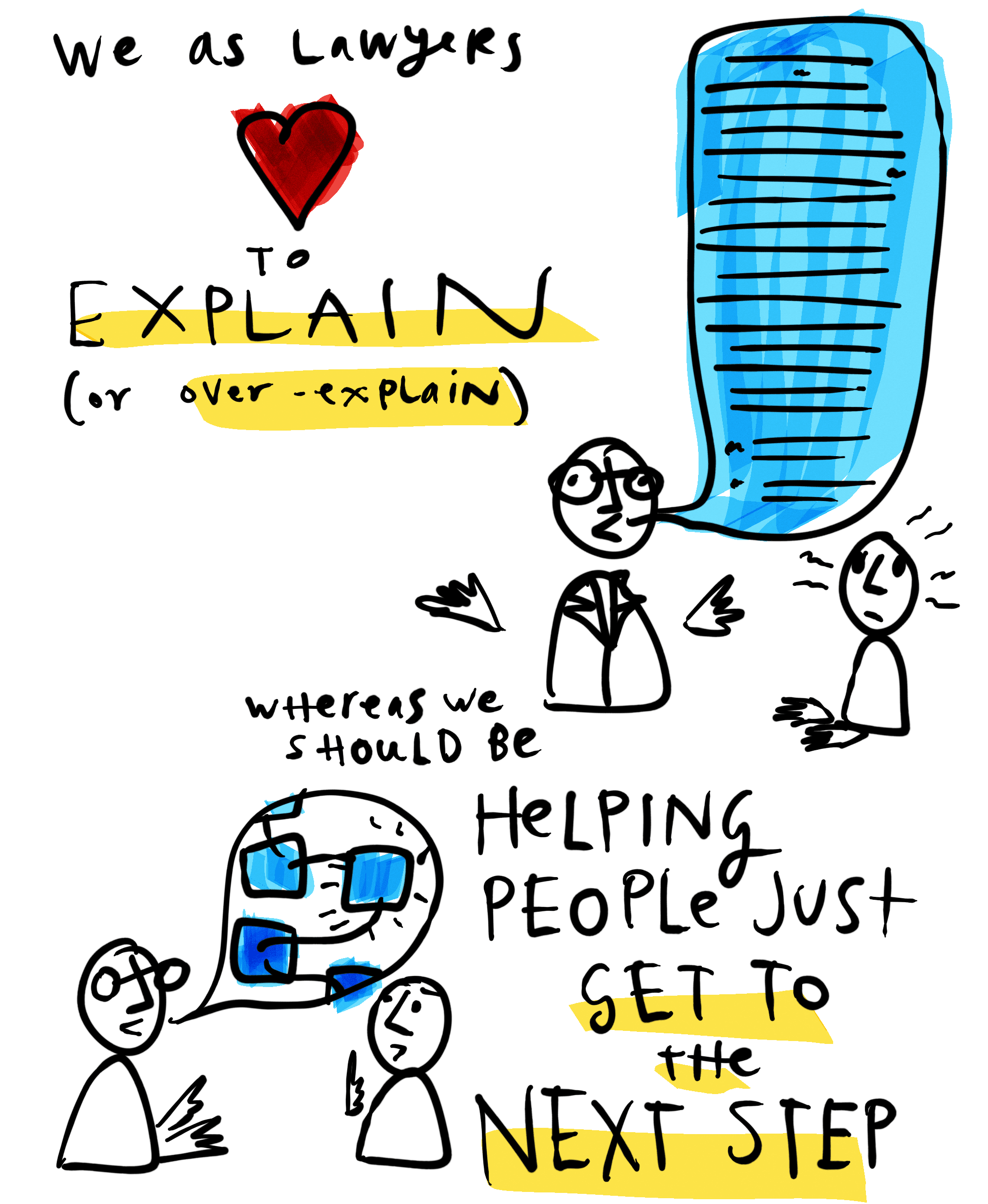

Corporate lawyers can learn from the design community. We as lawyers make complex information products — memos, law school textbooks, briefs, decisions. These have high cognitive load — long paragraphs of text, with footnotes and annotations, in huge amounts of abstract concepts.

But lawyers aren’t alone in figuring out how best to communicate complex things. What about graphic designers, signage and way finding work?

We as lawyers could be way-finders, and we should be borrowing from other folks who are taking on complex information challenges. They have studied how people intake information, how their eyes move across pages, how they react to instructions.

Caring about document design is serving our clients

We should be thinking about typography, about document design. Even though we are professional writers, we aren’t doing that.

Would we rather have our audience read Some of Less or None of More.

Typography is about the reader, not about the writer. It is about treating reader attention as precious, not presuming that we will have it easily and without work. We need to pay attention to design to

Design in the Law School Clinic

At our Transactions clinic, we take this approach with our work product and class materials. Our clients notice, and they really like it. They say that our stuff is easy to use. Lawyers don’t usually hear that.

Paying attention to design, brings a sense of craft to our work — we are making products for people, that they will use and work with. That ‘craft’ motive is very important — to think of ourselves as people who produce work product for people to use.

We take a Plain English tone — not conversational, but almost. We don’t use long

Some Final Thoughts

Even if the contracts and the official legal documents are never going to change, even if they will stay in the same formal, legalistic, traditional way for the next millennium, that’s not to say that design is irrelevant to lawyers. What about the client communications? We can redesign, with more graphics and more liveliness, how we help people use the materials, learn them, and act on them.