Ida Benedetto talks with the Open Law Lab about how she helps people understand issues of consequence through a combination of play and surprise. As a founder of Antidote Games, she develops diverse games for NGOs all over the world. She recently created a game, Accused, that gives players a taste of the police interrogation process. In case you haven’t, please play this game before you read further.

Ida was interviewed by Nikki Zeichner, a lawyer studying Integrated Digital Media at NYU.

Can you talk a little bit about Antidote?

Yes, we like to say that Antidote Games creates “playful experiences for complex realities.” Antidote Games typically works with humanitarian organizations that are working to address social and environmental problems all over the world. Our clients want to change behavior and they hire us to create tools that facilitate this change.

So you create games in order to bring about change.

To some degree. We make games that help people reach new perspectives through the consequences of their own choices. These new perspectives can often be the first step to changing behavior. More specifically, the transformative power of games that we deploy involves people surprising themselves with their own behavior. The game is a microcosm of a complex system that is out in the world. And the surprise is the pay off for the play. Our games are about giving people an access point into understanding these systems. We create that play from everything from a fantastical scenario online to beautiful analog game pieces that entice people to try something new.

But often times the new worlds that you create for your players seem distant from the social or environmental issue at the heart of the game.

Yes, we don’t want our players to know what was going to happen next. We want them to have an experience of feeling something new. New experiences develop new understandings and empathies.

You recently developed a game about interrogations faced by criminal defendants.

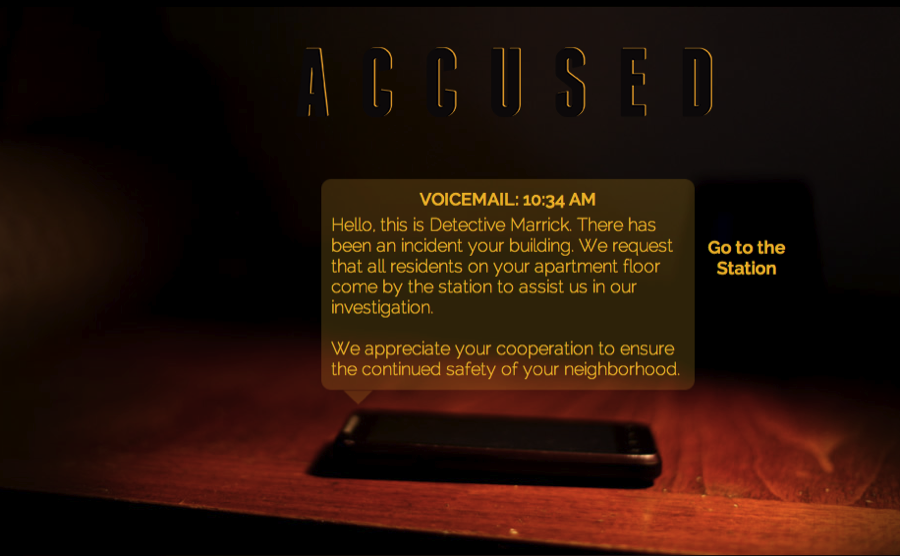

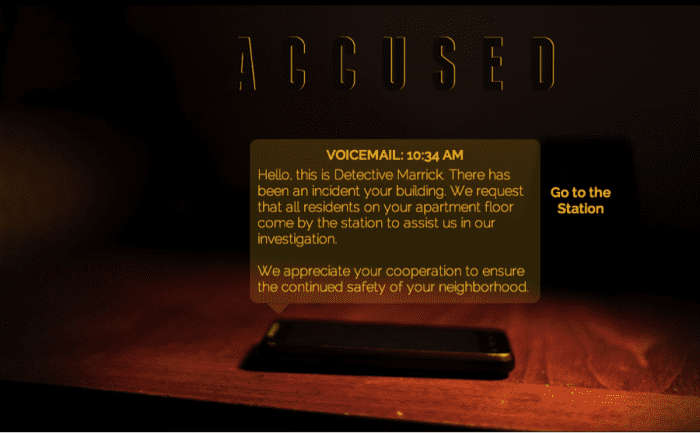

Yes, it’s called Accused. In Accused, we created a situation in which players are lulled into an interrogation. Players start out by talking with the police to help out a neighbor. They likely have pure motives, but in the questioning process, something changes and the police start treating the player like a suspect. No matter what the player tries to do to display innocence, the interrogators push for a confession. The circumstances arise that would lead someone to falsely confessing.

How did you come to develop this project?

We were funded by NYU-Stern to develop Accused in partnership with the Innocence Project. The problem that we wanted to address with Accused was one that we learned from doing preliminary research: people who confess typically are convicted at trial regardless of other factors that might point to that person’s innocence. People who sit on juries usually don’t understand why someone would confess to a crime they didn’t commit. You can have DNA evidence, testimony from witness, all sorts of evidence to the contrary but a jury will still be swayed by a recorded confession. We created Accused to develop understanding and empathy for people who break down during police interrogations and make false confessions.

Did the issue of police interrogations lend itself to gamification?

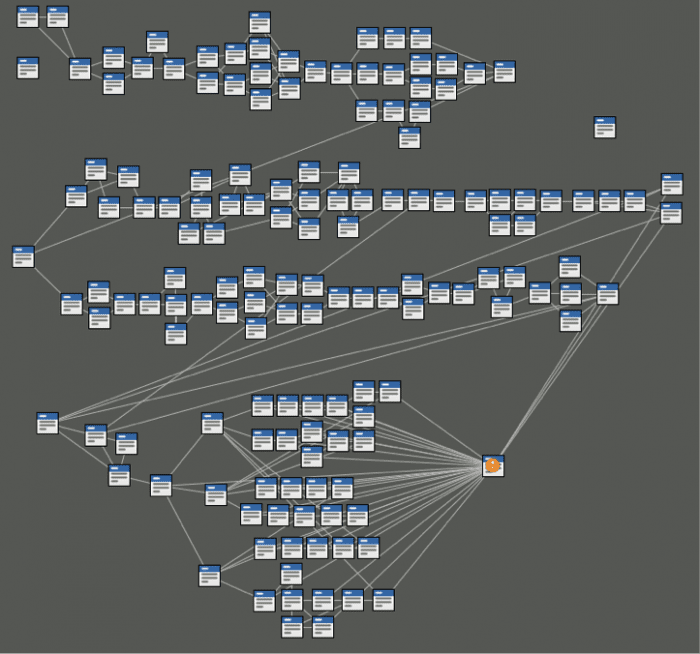

It did – games work particularly well in teaching people about clear systems. So regarding police interrogations, U.S. law enforcement commonly uses what is known as the Reid Technique, which is a systematic method intended to lead a suspect to confess. It’s been criticized elsewhere in the world including by a judge in Canada for too easily soliciting false confessions but that’s a side note. We found Reid Technique training videos on YouTube and we saw clear routine steps that law enforcement goes through when it interrogates suspects. These steps were easy to map into a game. This is a spoiler alert – I hope people play the game before what I’m going to explain now . . . if you look at the diagram of the game, you can see that all the pages lead to one separate page in the lower righthand corner. That final page is the confession page. This diagram shows the structure of our game, which parallels the structure of the interrogation technique that our law enforcement officers are trained to use.

What about the external factors that a person experiences only when they are actually in police custody. Can a game that someone plays voluntarily really communicate the complexity of the experience?

We designed the game to make the player aware of these factors and to feel them, even if they might not be as intensely felt as they would be in a real interrogation. We designed Accused to be nimble and lightweight in getting these pressures across.

Do you think that there are benefits to making the experience lighter?

Yes. The lightness creates an entry point and making it lighter increases our ability to reach more people and get more people to play. In the end, we’re developing greater understanding around the issue so long as people play the game.

And once you play the game, you’re better equipped to start approaching the system.

That’s right. After having a play-based experience, you’ll approach the information with a sense of recognition. For example, someone who played Accused might look at the phases of interrogation and they will seem familiar because they will have already had that emotional, playful experience with it.

What program did you use to create this?

We used Twine. It’s a popular tool right now and its open source which we like. If you want to modify it, you need to know Javascript so we worked with someone who is great at Javascript. But if you are fine leaving the structure as is, you don’t need to know code.

What’s next with Accused?

We’ve been exceptionally moved by our work on developing a project around false confessions and we want to expand Accused’s reach. I see the value of this game as being broad and we’d love to find organizations, educators, or activists who would use this. We’re particularly interested in developing support materials if we find the right partner to actually create a lesson plan of what these confessions look like and how they work.

And what’s next for Antidote Games in a more general sense?

In terms of our future games, we would love to be become increasingly less literal; we want to do a game for an NGO where the narrative is completely separate from the topic being discussed. A lot of times our clients are very concerned with conveying a particular message and so they’re very literal with what they want the game to actually talk about. I understand why they start off at this point, but really, you’re able to reach a larger and more diverse audience when you use a fantastical narrative. Do you remember when the CDC campaigned for emergency preparedness with the “Zombie Apocalypse?” The zombie hook that they used increased the campaign’s popularity while addressing the same issue.

So you need clients who are willing to take a risk.

Yes, a very worthwhile risk. Another thing we want to do in the future is to get support to do further assessment of our work. There is a lot more to do to demonstrate the power of games. There is a growing number of assessments for games in the learning context, but not so many on games like ours.

You create a diverse range of analog and digital games. What are clients asking for?

Organizations are looking for behavior change. Games are becoming increasingly respected for their ability to change behavior, be that with farmers in the South who are suffering from climate change and need to adapt their lifestyles – the Red Cross is having us a develop a game to address this issue; or in the case with Accused, where the behavior change is to reduce the common stigma that is associated with making confessions while being interrogated.

Creating a space for new experiences through play. . . would you say it’s about creating disorientation?

I like that. It shakes people up a little bit. And it’s refreshing for me too. We create constraints and possibilities and what people do with that depends on what they bring to that experience. So I get to be constantly surprised by learning new things from our audiences and our players and that’s some thing that I love. I don’t find much satisfaction in being the author.

I think it’s different from other more aggressive or controversial ways that people shake things up.

Yes, there’s a lot more wonder and joy in this approach. And people have to opt in. It only works if you continue to play. So the consequences of the game come from play. That engagement and investment opens up doors for more understanding but first someone has to enter into the game.

With law, you’re trying to get someone to see your perspective. You’re not just teaching someone information; understanding is at the heart of it.

Right, with law and with advocacy in general. That’s one reason why games can be great tools in helping people develop new perspectives about legal issues.

You can contact Ida at ida [at] playistheantidote.com